The Inner Light of All Scripture

Dr Sabine Hyland, Reader in Social Anthropology

10 December 2017

Readings: Hebrews 1: 1-4, John 1: 1-9

Thank you to Donald, and to the community of St Salvators Chapel for this very gracious invitation to preach here today. It’s an honour to be at St Salvators, and to speak from the pulpit where, according to legend, 458 years ago my direct ancestor John Knox delivered the infamous sermon that led his audience to rise up en masse and tear down the cathedral. I promise you that there will be no rioting advocated this morning, and you can remain in your seats at ease. Instead, I’d like to talk about the Gospel reading — one of the most beloved and challenging of all the traditional Christmas readings — “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God”. This passage from John continues with an unforgettable description of the Incarnation, of the event that we celebrate at Christmas: “And the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us”.

To put it another way, Christ, who is God incarnate, is also the Word — the Logos — which can be translated as Divine Reason, and by extension as “Wisdom”, as the moral law written in all human hearts. Christ as the Word, the ultimate source of Wisdom and Philosophy, is the “light that shines in the darkness, and the darkness shall not overcome it… the true light that gives light to everyone”. Wow, what does this mean and what are the implications? St Justin Martyr, the 2nd century Church father and Christian apologist, wrote that those who have not accepted Christ but who follow the Word — that is, the Logos or wisdom in their hearts — follow God because God has planted the seed of moral truth in the hearts of all nations. Nations who have never heard of Christ, such as the ancient Greeks, still had access to divine truth. In his works, Martyr showed, as have many centuries of subsequent theologians, that the writings of the ancient Greek philosophers illuminate and expand our understanding of Christian truth. The apostle Paul, in his letter to the Romans, emphasises that God has implanted an innate knowledge of himself in all nations and all peoples. As Nostra Aetate, the Second Vatican council’s declaration on the relation of the Church to Non Christian religions states, “From ancient times down to the present, there is found among various peoples a perception of that hidden power which hovers over the course of things and over the events of human history… This perception and recognition penetrates their lives with a profound religious sense”.

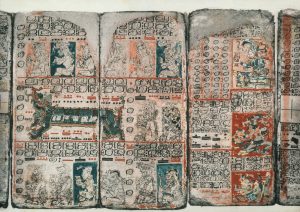

Well, how does an anthropologist like myself, dedicated to studying the native peoples of the South America, respond to this? As you know, for over 600 years, St Andrews has been a centre of research and commentary on the Christian scriptures, with the aim of nourishing Christian spiritual life. Generations of renowned Scripture scholars have processed into this very chapel every Sunday for hundreds and hundreds of years. What you may not know is that the indigenous peoples of the Americas have their own Scriptural traditions, inscribed onto birch bark, twisted into deer hair cords, and even written in books made of fig bark paper, and bound between jaguar hide covers, all dating to long before the arrival of Europeans to the Americas. The ancient Mesoamericans, for example, wrote books made of fig bark paper, known as huun, folded accordion style (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dresden Codex

The Mayan texts, or codices as we call them, contain hieroglyphic writing that describe the nature of ancient Mayan rituals, astronomy, cycles of time, divination and other matters. The image in Figure 1 is of the Dresden Codex, written about 400 years before the first Spaniards arrived in Mexico. This 12th century book contains descriptions of the Rain God’s palaces, instructions for the New Year’s ceremony, and tables tracking the movements of the Moon and of the all-important planet Venus, noh ek, the shining warrior who was the reincarnation of one of the hero twins, Hunapuh, who with his brother defeated the Nine Lords of the Underworld.

As an anthropologist, I believe that these indigenous scriptures contain ancient wisdom which can illuminate and expand our notions of god and divinity. The sacred scriptures of the Americas contain an inner light of truth, and anthropology opens the door for us to understand this truth. In ancient Mesoamerica, the power of the wisdom in their hieroglyphic books was readily acknowledged; here, for example, is a Nahuat description of a man who was learned in the pre-Columbian Mexican scriptures:

“The wise man: a light, a torch, a stout torch that does not smoke.

A perforated mirror [to scrutinise all things];

His are the black and red ink, his are the illustrated manuscripts, he studies the illustrated manuscripts;

He himself is writing and wisdom;

He is the path, the true way for others…

His is the handed-down wisdom; he teaches it; he follows the path of truth.

He applies his light to the world.”[1]

We are now able to read many of the Mesoamerican hieroglyphic books; the decipherment of the Mayan glyphs in the last decades of the 20th century has allowed us to begin to glimpse the lost writings of this ancient world, one whose descendants, however, carry on deeply rooted religious traditions.

For the Andes of South America where I work, however, we are still struggling to decipher the indigenous writing system — the mysterious knotted and twisted cords known as khipus (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Khipu in Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford. Photo by author.

These khipus were used to record accounts, histories, poetry and even letters sent from one person to another in the Inka Empire, the Andean kingdom that was conquered by the Spanish in the 16th century. We used to think that Andean people abandoned the use of khipus at the time of the conquest, under duress from Spanish officials and missionaries who burned khipus and made their use illegal. What I and a couple of other anthropologists have discovered, however, is that there are at least a handful of very remote villages in the Andes where people continued to use khipus for communication up until the middle of the 20th century. We still haven’t fully deciphered the khipus, although some of us have made progress in that direction. So I can’t end my sermon today by regaling you with accounts of the wisdom that may be contained within these books of twisted fibre.

However, working in an inaccessible part of the Central Andes with my husband Bill, supported by National Geographic, we were able to document a sacred ritual manuscript written by Andean villagers about 100 years ago, a work that describes the villages’ major annual ceremony in honour of the earth mother, Pachamama, of the mountain gods, and of a type of supernatural person known as an “earth being” (“huaca“). Khipus played an important role in these ceremonies in the past when this sacred text was written, although their place has now been taken by records written in pencil and ink in inexpensive notebooks.

This holy scripture, about 60 pages long, provides guidance for the how the villagers must regulate their relationships with the sacred forces around them. No outsider had ever been shown the manuscript before, although rumours of its existence swirled amongst anthropologists in this region. The villagers who revere this manuscript as their sacred scripture live at an altitude of 11,000 feet, with fields and pastures in the clouds at over 13,000 feet. The roads are unpaved, the houses are all made of mud brick, and villagers still get around primarily on donkeys and on horseback. But with incredible graciousness, the President of the community allowed me and Bill to have access to the manuscript for 24 hours to read it and to photograph it, which was extraordinary. When we went to hand it back to the President, as we were waiting in his office for him, we encountered another local man who stroked the worn cover of the manuscript reverently and told us, “everything that anyone could ever need to know is in this book”.

I’m currently working with a team of scholars here at St Andrews to transcribe and analyse this sacred text, and we still have a long way to go towards understanding it. One of the aspects that is becoming clear, however, is the very special way in which the landscape around the community is regarded through the text, and throughout the ceremonies it recounts. The land is not an inert, utilitarian feature, but is the boundary through which the sacred emerges into the human world in specific powerful places. These places mark where “earth beings”, supernatural male and female ancestors, surface into our “pacha” — the single word that denotes both time and place. In some of these hallowed spots, particular khipu records must be knotted to memorialise the place every year; it is not only that the landscape itself is animate, pulsing with life, but that the khipu cords made there themselves become imbued with the spirit of life. We know that for the ancient Mayans, books had to be ritually purified, sanctified and treated as individual personalities — it seems that the same may have been true for the fibre khipu texts in the Andes, at least for those containing sacred knowledge.

The places of power in the landscape where earth beings erupted from the interior and into the surface world are known as “pacarinas“, that is, places of origin. These special sites are often referred to as “windows” (“tocco“) in the landscape through which the gods emerge for the first time into our time and place, which is one word in Quechua: pacha. These sites are still revered for giving rise to beings like a local ancestress known as Chaupi ñamca, who causes the spring waters to flow, irrigating the crops in the otherwise barren mountains. The same imagery for how the supernatural earth beings like Chaupi ñamca spring forth from the landscape is used in the Andes to describe how Christ became incarnate, emerging into our world in the exact same way, through the pacarina — the place of origin and the window — of his mother Mary’s sacred womb.[2]

If we believe that indigenous Scriptures contain natural wisdom and natural theology, we are enriched as we study these difficult and often challenging texts.

Christ as the Word is greater than what Western philosophy and theology alone can reveal. When we read the sacred scriptures of indigenous America, it is missing the point to try to fit the lessons of these scripture into already established categories of Christian religious thought — for example, trying to find vestiges of the idea of “God the Father”, or of the Trinity, and then leaving our analysis there. As a Christian, I believe that we must strive for an analogic theology that views life in terms of both/and, rather than either/or. And if the theological complexities of such a position seems overly daunting, trying to understand the inner light of a multiplicity of sacred scriptures rather than of just one — well, we better get cracking then! The potential rewards will justify the effort, for a theology rooted in natural wisdom, one which rejects Western hegemony in favour of a truly universal Christianity in which all the peoples praise God, each nation singing in its own unique voice, each enriching the universal choir of joy.

[1] Miguel Leon-Portilla, Native Meso-American Spirituality, Classics of Western Spirituality, Paulist Press, 1980

[2] The use of the tocco and pacarina imagery for the Incarnation of Christ can be found in Francisco de Avila’s Quechua Christmas sermon on the prologue to John’s gospel. Francisco de Avila, Tratado de los evangelios… Lima, 1648.